Inside Beyrouth

A little bit of Lebanon in Amsterdam

By Sharida Mohamedjoesoef for the Amsterdam Weekly (issue 26 July - 2 August 2006)

Most people know him as the jovial owner of the Lebanese restaurant Beyrouth in the Kinkerstraat. And even now, while his country is being pounded unrelentingly by Israeli bombs and his own relatives are bearing the brunt of the wrath, he is still his usual charming self: Kamal Estephan, born in

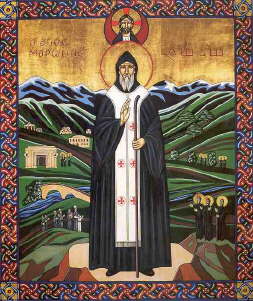

The walls in Kamal’s restaurant are covered with various rugs, a detailed map of his native country and if you look even closer, there is a small picture of Mar Maroun, the fifth-century Lebanese hermit considered to be the father of the monastic movement now called the Maronite Catholic Church. But what stands out most is the posters of the capital Beirut before the civil war; a war in which the capital city image as the Paris of the Middle East was blown to smithereens by car-bombs and kidnappings.

Kamal was only 11 when he witnessed the onset of the civil war in

Estephan goes on to explain: “The economic factor was another major obstacle. You have to realise that the Lebanese civil war was very much a battle between the haves and the have-nots. For a long time, the Lebanese Christians enjoyed greater prosperity, because they had smaller families and were therefore able to give their children a proper education. “The irony of it all, is that

Estephan grew up in a country that was characterised by a peculiarly structured political powerhouse which also helped fuel growing unrest among the Lebanese. The president always has to be a Maronite Christian. The prime minister should be a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of parliament a Shia. This was fine, until the early 1970s when there was a gradual shift in the demographic make-up of the country. Christians were soon outnumbered by the Muslim population. Add to this the PLO-factor and you have all the ingredients that led to a bloody civil war.

“This war ended in 1991. But if Lebanese society is so much better? Mmm… I doubt it. Some of the problems that lay at the heart of the civil war, are still very much there. True, interreligious interaction has definitely improved. But nonetheless, it is still a far cry from what it should be. And with the war

Estephan is clearly distressed by what he sees happening for the second time in his life. He’s not afraid of apportioning blame, but sees fault on all sides of the divide: “Three words come to mind: guilt, aggression and revenge,” he says. “Let me start with the guilt: everybody, from